From the Travels of Ibn Battuta.

That night, while I was sleeping on the roof of the cell, I dreamed that I was on the wing of a great bird which was flying with me towards Mecca, then to Yemen, then eastwards and thereafter going towards the south, then flying far eastwards and finally landing in a dark and green country, where it left me. I was astonished at this dream and said to myself “If the shaykh can interpret my dream for me, he is all that they say he is.” Next morning, after all the other visitors had gone, he called me and when I had related my dream interpreted it to me saying: “You will make the pilgrimage [to Mecca] and visit [the Tomb of] the Prophet, and you will travel through Yemen, Iraq, the country of the Turks, and India. You will stay there for a long time and meet there my brother Dilshad the Indian, who will rescue you from a danger into which you will fall.” Then he gave me a travelling-provision of small cakes and money, and I bade him farewell and departed. Never since parting from him have I met on my journeys aught but good fortune, and his blessings have stood me in good stead.

Here’s a new narrative:

WHEN Malcolm X visited Mecca in 1964, he was enchanted. He found the city “as ancient as time itself,” and wrote that the partly constructed extension to the Sacred Mosque “will surpass the architectural beauty of India’s Taj Mahal.”

Fifty years on, no one could possibly describe Mecca as ancient, or associate beauty with Islam’s holiest city. Pilgrims performing the hajj this week will search in vain for Mecca’s history.

The dominant architectural site in the city is not the Sacred Mosque, where the Kaaba, the symbolic focus of Muslims everywhere, is. It is the obnoxious Makkah Royal Clock Tower hotel, which, at 1,972 feet, is among the world’s tallest buildings.

This opinion piece from the New York Times describes the complete destruction of the historical landscape and architecture of Mecca and its consequences for the hajj. It emerges out of a form of iconoclasm, the fear that sacred images usually – but in this case sacred places too – encourage veneration of the human, the tangible, the thing, rather than God.

|

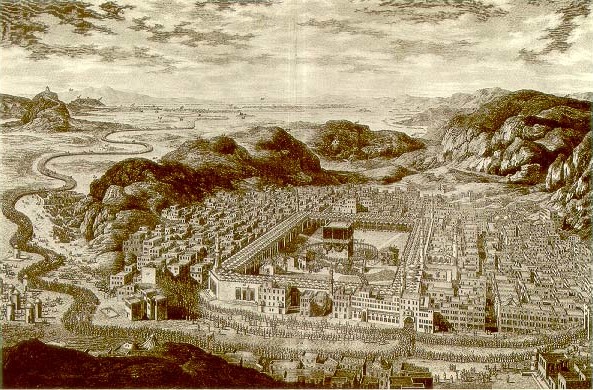

| Mecca in 1850 |

It’s also a new phenomenon, this kind of erasure of a sacred past, at least in Islam. One hears, all the time, about the Muslim dislike of figural images, especially the controversy about images of the Prophet. In fact, Muslims have produced thousands of images (probably more) of the prophet over the centuries (click here for a big archive) as well as many other figural images. Other Muslims have destroyed such images, have demanded only geometric art, and so forth.

These are questions of debate and interpretation and they have a long history. But there’s a reason that the Buddhas in Afghanistan stood for 1700 years, much of it in Islamic hands, before being destroyed by the Taliban. There are reasons that ISIS has defaced many ancient landmarks, though they are also quite happy to sell pre-Islamic artifacts on the black market. And Saudi Arabia’s leaders are destroying Mecca’s past, in the interest of extremism, profit, and control. [my emphasis in the following]:

The only other building of religious significance in the city is the house where the Prophet Muhammad lived. During most of the Saudi era it was used first as a cattle market, then turned into a library, which is not open to the people. But even this is too much for the radical Saudi clerics who have repeatedly called for its demolition. The clerics fear that, once inside, pilgrims would pray to the prophet, rather than to God — an unpardonable sin. It is only a matter of time before it is razed and turned, probably, into a parking lot.

The cultural devastation of Mecca has radically transformed the city. Unlike Baghdad, Damascus and Cairo, Mecca was never a great intellectual and cultural center of Islam. But it was always a pluralistic city where debate among different Muslim sects and schools of thought was not unusual. Now it has been reduced to a monolithic religious entity where only one, ahistoric, literal interpretation of Islam is permitted, and where all other sects, outside of the Salafist brand of Saudi Islam, are regarded as false. Indeed, zealots frequently threaten pilgrims of different sects. Last year, a group of Shiite pilgrims from Michigan were attacked with knives by extremists, and in August, a coalition of American Muslim groups wrote to the State Department asking for protection during this year’s hajj.

The erasure of Meccan history has had a tremendous impact on the hajj itself. The word “hajj” means effort. It is through the effort of traveling to Mecca, walking from one ritual site to another, finding and engaging with people from different cultures and sects, and soaking in the history of Islam that the pilgrims acquired knowledge as well as spiritual fulfillment. Today, hajj is a packaged tour, where you move, tied to your group, from hotel to hotel, and seldom encounter people of different cultures and ethnicities. Drained of history and religious and cultural plurality, hajj is no longer a transforming, once-in-a-lifetime spiritual experience. It has been reduced to a mundane exercise in rituals and shopping.

I want to note that I put the Taliban, ISIS, and the Saudi Salafis in a single paragraph above. I am doing it again here. The Saudi government has long struck a deal with their extremists – they give them a safe place to live, they give them money, they give them power over religious expression, and in exchange Saudi doesn’t face the kind of extremist pressure seen in other Sunni countries. It’s been a good deal for the government; it’s been bad for the world, it’s been worse for Islam, and now it’s destroying Mecca.

There have been long period in Islamic history were pluralism was the default – not just strains of Islam, but many other religions as well. This is the prime target of extremists – not really “The West,” or Israel, or Christianity, but other forms of Islam.

I am struggling to find any analogy from history to the utter destruction of the historical landscape of Mecca. Even in the great moments of iconoclasm, when images were destroyed, whole landscapes remained intact, in part because technology didn’t exist to erase them. The particular relationship with sacred space – the urge to turn it into shopping malls and packaged tours – is riveting and terrifying.

It’s also inexorable. Mecca, the holy city, will be Mecca the Mall, gleaming and modern, air conditioned, effortless for the rich, unobtainable for the poor.