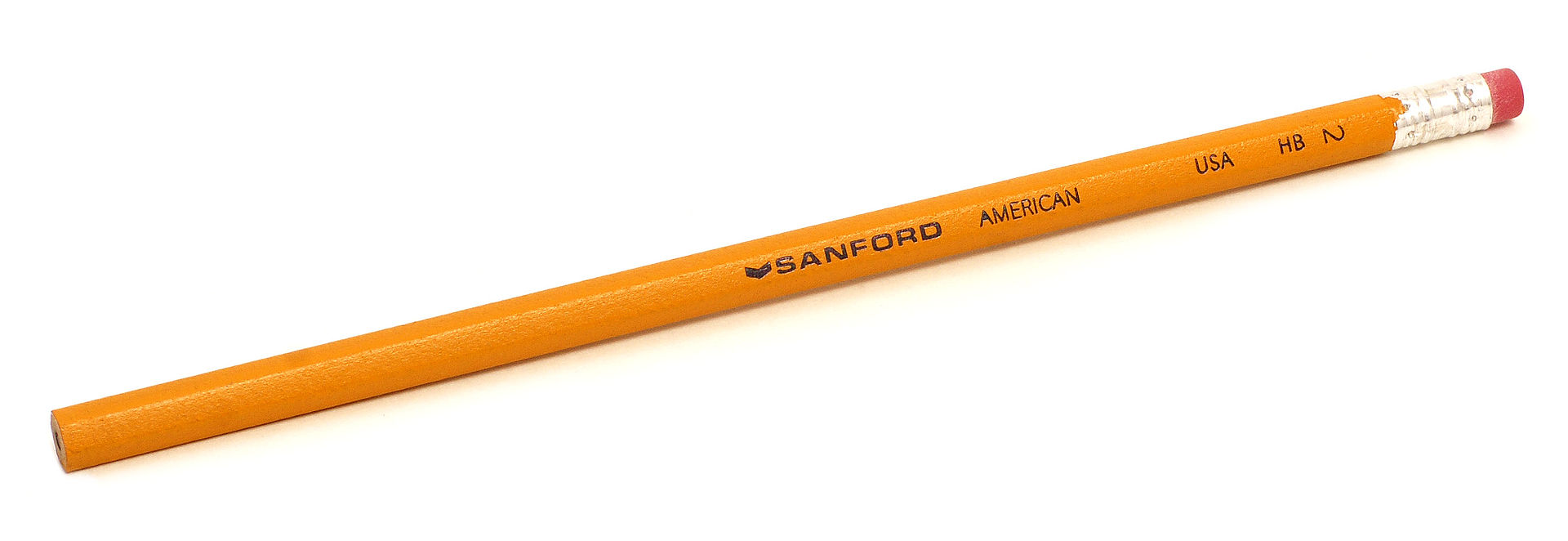

The apartheid government of South Africa had a problem (well, it had a lot of them, but bear with me). It wanted to discriminate by race, but how does one deal with mixed-race people? It came up with the infamous “pencil test,” in which a pencil is pushed through a person’s hair, and how easily it emerges determines the classification. The pencil test is penetrative, with overtones of the state’s control over black bodies medically, sexually, and in so many other ways. For me, it’s always been a symbol of the whole evil apartheid construct.

It’s been on my mind lately because of a broad discussion about disability and fakery. How disabled must a person be to qualify as “disabled” under the law? Being disabled comes with certain civil rights protections. Being disabled to a certain degree entitles one to a check from Social Security every month. Being disabled, as Justin Bieber knows, can enable one to skip lines at Disneyworld (instead of linking to Gawker or TMZ, why not read the great Emily Ladau on Bieber). Being disabled, in the eyes of the abled world anyway, comes with advantages (great parking!), sympathy (oh, your son is cute), and money.

This is, of course, nonsense and tracks to the ways that other privileged groups envy the perceived benefits of those who experience discrimination. In the disability world, this often tracks to “how disabled are you really?”

We saw it recently with George Takei’s ill-conceived posting of a picture showing a woman standing on her wheelchair to get down a bottle of alcohol in the grocery store. The caption, “There’s been a miracle in the alcohol isle,” suggested that this woman wasn’t /really/ that disabled if she could stand on the wheelchair to get some booze. Disability advocates protested and Takei initially told them to lighten up, which is the first response of so many comedians when called on humor that replicates stereotypes. I was first alerted to it by a friend who can walk about 100 feet before using her wheelchair, and she told me that she lives in fear of being accused of faking and having to defend her disabled state.

There were a /lot/ of articles about the meme and Takei. I thought this one from Scott Jordan Harris at Slate was especially good when he offered an alaternative read of the scene. He wrote:

“Someone with the Twitter handle @Andy00778. wrote that the picture shows how “much fraud there is today,” adding “Hope insurance company see it!”

The picture does not show fraud. What it shows is a disabled person using a tool—her wheelchair—to live independently. If any judgement is to be made about the photo at all, it should be celebrated for showing that independence.”

Eventually, Takei apologized, at length and sincerely, and the story faded.

I’m writing about this because a 2008 story just made its way to my feeds. I’ve been working hard on the issue of disability and police violence, but I don’t claim to have a master database or anything like a total set of examples. In 2008, my son was one and I was just beginning to apply my training as an academic to disability issues. I wasn’t even on Facebook yet.

Here’s the story and the post. In it, a cop doesn’t believe that someone arrested on a traffic violation is /really/ disabled, so he decides to conduct his own test, dumping him on the floor (and breaking some ribs). This is the extreme case, but it’s the same as the Takei meme in its origins (eventually there was an apology and probably a lawsuit).

Our language and our actions around disability and fraud matter. They ripple through the culture, shaping behaviors and ideas beyond. Language – comedy memes – have power.

(function(d, s, id) { var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = “//connect.facebook.net/en_US/all.js#xfbml=1”; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); }(document, ‘script’, ‘facebook-jssdk’));