Apparently there’s a new show on Netflix called Derek. I haven’t watched it. Who has time to watch that sort of thing in between parenting, working, writing, cooking, cleaning, gardening, sports, cooking shows, and all the other things that fill up my life.

Apparently, though, it features a lead character who is unbelievably good and presumably has a disability. It falls into the “angel” side of what I like to call the “Angel/Retard Dialectic” (discussed in this CNN essay). I’m very interested in the way that positive stereotypes, as nice as they can feel, are just as limiting as negative stereotypes.

Here’s a review, then I’ll offer a few comments at the end:

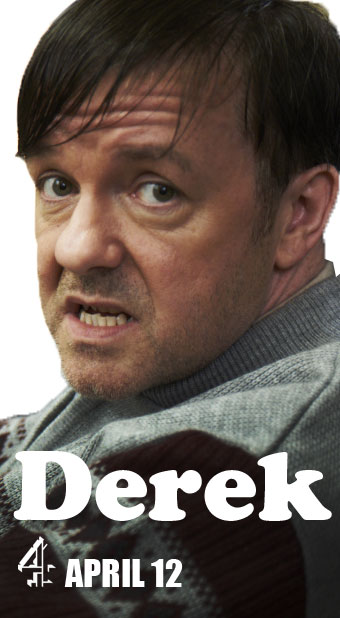

Derek, played by Ricky Gervais, is an incredibly nice person who may or may not have a disability.

Derek is what his friends and co-workers euphemistically refer to as

“different”: He walks with a shuffling gait, he has a chronic underbite,

and he is unable to maintain eye contact with others. His physicality

has led the show’s minor characters (and its audience) to infer that he

is mentally disabled (Gervais, who created the character in 2001, insists that he is not).

Whether or not he is, however, is secondary to the fact that he is

clearly differently abled in some way, a distinction that the show’s

creators conflate with kinder, better, and more generous than the lion’s

share of humanity. [my emphasis]

The author continues:

With his near-divine capacity for goodwill, Derek is exemplary of

Hollywood’s tendency to canonize the differently abled. Like Forrest

Gump or Chance the Gardener or the title character from I Am Sam

before him, Derek is an MPDAP (Manic Pixie Differently Abled Person).

MPDAPs don’t drink, smoke, or have any sexual desires; they exist solely

to stand in contrast with the callousness and cynicism of the

“mainstream” world ….The MPDAP change the lives of those

around them by the force of his decency and goodness — and, perhaps,

teach us audience members a valuable life lesson or two in the process.

Well, that all sounds charming, so what’s the problem, you are undoubtedly asking. I’m glad you asked:

The problem is that, like most generalizations about marginalized groups,

it perpetuates misconceptions about disabled people. Take, for

instance, the stereotype that people who have Down’s Syndrome are more

likely to be indiscriminately affectionate than those who don’t. While

objectively speaking, there are far worse stereotypes for a marginalized

group to be saddled with…such a trope dictates how other

members of society see these groups, thus depriving them of their

agency.

The review then tracks the MPDAP, as they have called it, through other iterations: Corky (Life Goes On), Cousin Geri (Facts of Life), and even the literal appearance of people with Down Syndrome as Angels:

There’s 7th Heaven, where the Camdens habitually refer to

characters with Down’s Syndrome as “angels” (a designation that was

rendered literal by the show Touched By An Angel, featuring a

performance by Burke as a “guardian of faith”). At no point do these

MPDAPs exhibit any human emotion other than pure decency, neither anger

nor frustration nor sexual desire. They might as well be inspirational

posters or cardboard cutouts in a middle school guidance counselor’s

office.

Really, you should just read the whole essay, which then turns to think about more complex portrayals recently – Glee’s sassy cheerleader with a gun, The Secret Life of an American Teenager and its engagement with Down syndrome and sex drives, Family Guy, and even South Park. I decided I had to stop watching South Park at one point, but the author makes the argument that:

The characters of Timmy and Jimmy, while subject to the same level of

scathing mockery as all other marginalized groups on the show, don’t

exist as objects of pity or fetishization: they’re well-assimilated into

their social circle, they’re capable of feeling emotions other than

Derek’s brand of unconditional love and decency, and they pursue their

interests while rebuffing anyone who attempts to valorize them for doing

so.

I’m not sure I can watch Timmy and Jimmy anymore, but it is true that they fall outside the “angel/retard dialectic.”

I’m going to give Derek a pass – again, who has the time? But it’s worth thinking about the “super-crip,” the MPDAP (it refers to the Manic-Pixie Dream Girl TV trope), and all the complex forms of inspiration porn that shape disability and representation. In my original essay on the dialectic, I wrote:

Symbols, labels and representations — in media, literature and our

daily conversations — shape reality. The words “retard” and “angel”

represent images that dehumanize and disempower. Both words connote

two-dimensional, simple or limited people. Neither angels nor retards

can live in the world with the rest of us, except as pets, charity cases

or abstract sources of inspiration.

I stand by that. The key is to represent people with disabilities as people – or better yet to let them represent themselves – so they can live in the real, complex, often inconsistent, real world with everyone else. That’s the pathway to inclusion.